Welcome to Country: Join Us on Our Kimberley Adventure & Meet Our New Partner in the Northern Territory

by: Jennifer Smith Grubb

The sun rises early in the Eastern Kimberley, and the birds have been whistling for the past hour. We rise early too. It’s the only way to beat the heat.

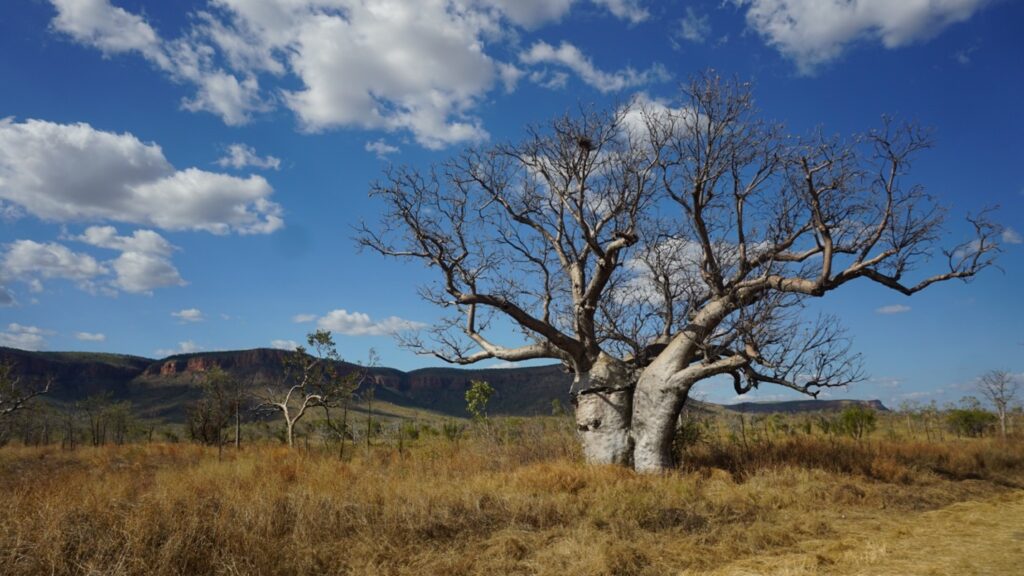

My husband Hugh and I have flown to the outback in northwestern Australia, driving west in a four-wheel drive vehicle on the famed gravel-covered Gibb River Road with the frontier town of Kununurra at our back, passing dramatic escarpments cutting huge swaths of rouge red against the sky. Puffs of white cloud hover above, stretching as far as the eye can see. Upside down trees, called boabs, with shapely trunks and stick arms reach out to greet us. Black kites soar overhead. The air is still, the sun is searing, it’s the end of winter and the cool weather has just evaporated into last week.

Our destination is Emma Gorge in the million acre El Questro Wilderness Park. Named for the wife of an early European explorer and known by the Aboriginal people for thousands of years, it’s special because of its refreshingly cool natural pool of water or billabong, fed by a 200-foot-high fern-encrusted waterfall. We hike for more than an hour from camp, fording meandering streams, scrambling awkwardly over chunky boulders, following strategically placed 3-inch-long marine blue arrows up and down, magically fastened to the rocks striated in rust and ochre-colored veins.

Rimmed on three sides by dramatic sheer rockface, the waterhole or billabong appeared like a mirage in the desert, so perfect and welcoming a respite from our rocky climb. We peeled down to our swimsuits and plunged in, ecstatic at finding this oasis. As we swam along the rock wall thick with forest green ferns, water sprinkled on us from above as if we were participants in a ceremonial blessing.

I wish you all could have been with us. Swimming under the waterfall, I gasped, laughing with delight and simultaneously shocked with the cold rush of water. Cleansed and euphoric, a tremendous sense of gratitude enveloped me as I swam. Floating in the blue mist, we eventually found our footing in the gravel at the water’s edge, emerged to don our hiking garb and made our way back to camp, forever changed.

In search of the elusive and rare Gouldian finch, we rose at dawn the next day to explore nearby Saddleback Ridge where the Crayola-splashed birds had been spotted the day before. Fording a major river in our four-wheel drive vehicle, we scrutinized the highest branches of the slender eucalyptus trees along the riverbank and watched the brown honeyeaters taking a bath. We headed along the stone pocked roughly hewn dirt road into the sun and the first ridge.

We parked at the foot of a steep incline and walked up the road toward the first switchback, marveling at the variety of birds traversing the deep and vast cavern which dropped down to our right, dipping down below us and soaring across the valley to a sheer red rock face in the distance and back over our heads in dizzying circles. We spotted a rock pigeon, rainbow bee eaters, and brown honeyeaters. But nowhere did we find a Gouldian finch.

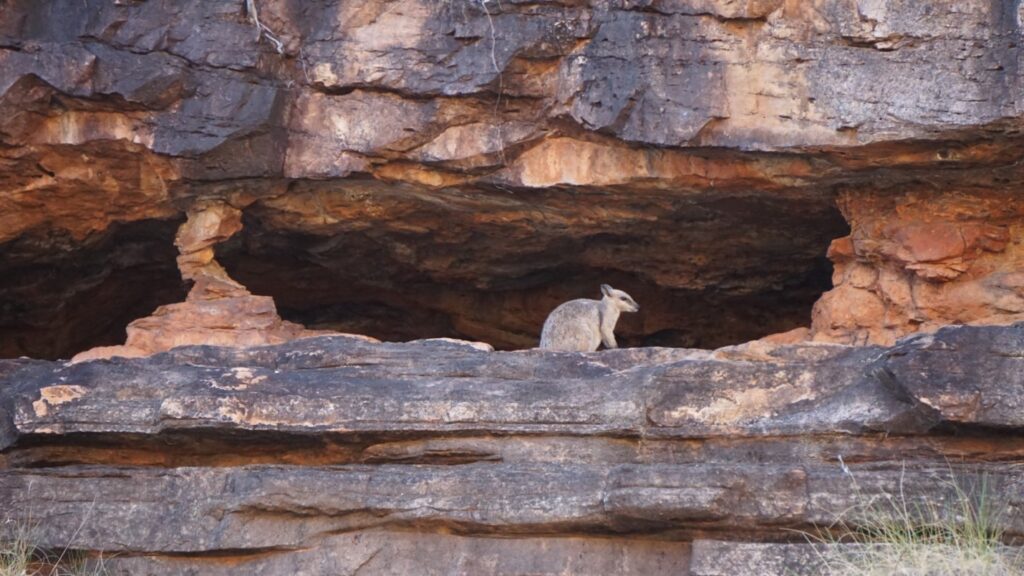

In the afternoon we boarded a 40-passenger flat bottomed boat with a shaded top for a guided tour on the Chamberlain River, through a high walled red sandstone gorge emerging from the earth in a sudden uprising 1,800 million years ago. Brush-tailed rock wallabies watched us from shady horizontal crevices high above, as we floated along the narrow river channel.

Sailing over our heads, little pied cormorants dove below the surface of the water. At the end of the two-mile stretch of water, we found Archer fish. Known for targeting their prey with accuracy, these fish shoot a stream of water from their mouths at their intended victims, in this case our extended fingers holding morsels of dried fish food. Schools of barramundi join the Archer fish, waiting for a fish snack to drop their way.

On our last morning, we responded to the call of the Injiid Marlabu and participated in an Aboriginal Welcome to Country experience at the camp at El Questro Station hosted by the Ngarinyin people. We were greeted by Mary Riri, husband Nelson and daughter Chanel, teaching the ancient ways of First Nations people who have lived on the continent for 65,000 years.

Nelson played the didgeridoo while Mary and Chanel bathed us in wafting smoke from the campfire they had made, guiding the smoke over and around us, introducing us to the elders of The Kimberley and cleansing our senses by gently laying their hands over our eyes “to see” (“mara”), the ears “to hear” (“nguru”), the nose “to breathe” (“ngoyba”) and the throat “to speak” (“wurla”).

Chanel called to the wind in low tones, as if with a conch shell, but only using the sound of her voice. The wind responded in a sudden breeze against our cheeks. Mary taught us the life-giving qualities of the native plants, like the paperbark tree. The leaves and bark are used to treat coughs, colds and wounds, applied directly or crushing and soaking in water to create a drink. Leaves and bark can also be burnt, and the smoke inhaled.

Nelson tells us of the heritage of a child’s animal totem, given to each unborn child by the father after a hunting trip or a dream, and manifested perhaps in a birthmark on the child’s body where the animal had been wounded and in traits of the child, the characteristics of the animal who has given its life, thus infused into the child.

Mary also shared sobering statistics about the Kimberley Aboriginal youth affected by fetal alcohol syndrome since the late 1960s, when a government financial stipend combined with ready access to alcohol became an unwelcome chapter in Aboriginal history in the Kimberley. The mothers kept asking, “What is wrong with our children?” until scientists studied the population, and they finally learned about the impacts of alcohol on their newborn children.

Aboriginal people have a profound connection to Country and Indigenous land rights are an issue at the forefront of Australian politics. In November of 2022, more than 600 square miles of El Questro Homestead were returned to the Traditional Owners through an historic Indigenous Land Use Agreement, 120 years after El Questro had been made a sheep station. The property is now leased back for tourism purposes.

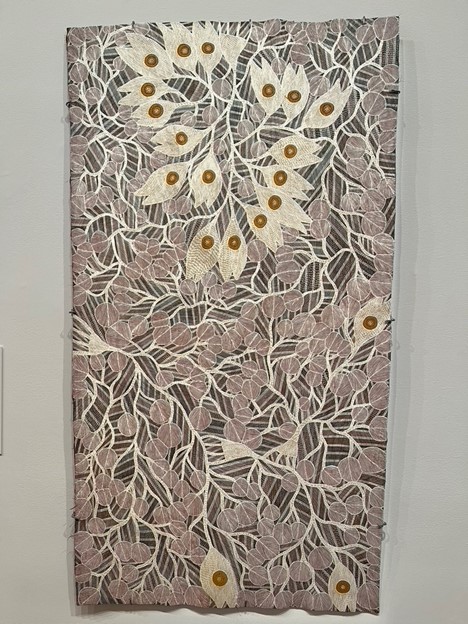

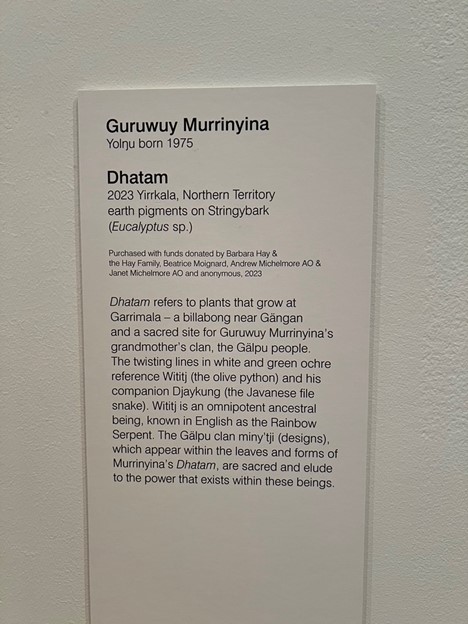

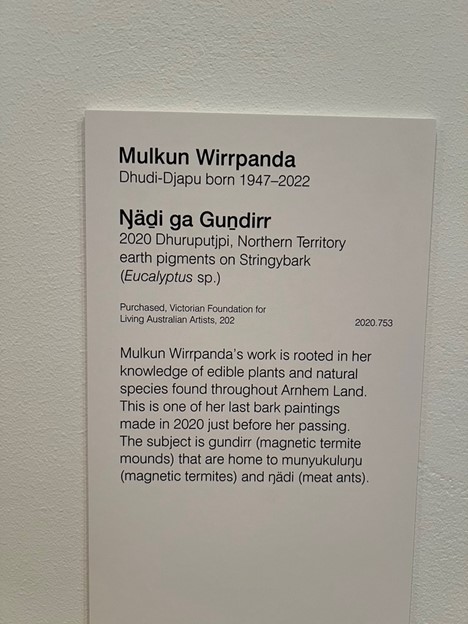

Almost 700 miles northeast of the El Questro Wilderness Park in the Northern Territory, Friends of the Australian Bush Heritage Fund is establishing a new partnership with Karrkad Kanjdji Trust (KKT). KKT was created in 2010 to support Warddeen and Djelk Indigenous Protected Areas on Arnhem Land. KKT supports Indigenous rangers to live on their ancestral homelands and manage Country across 25,000 square miles of highlands and savannah lowlands.

Aboriginal people are returning to Country across Australia, helping their youth to reconnect with the land and teaching the ancient ways. In Arnhem Land, they need help protecting native biodiversity, managing fire and climate impacts, investing in women rangers, safeguarding Indigenous culture, supporting people on Country and educating future custodians to care for Country.